Episode 22

Behind the Deep Fat Fryer: America's Original Fair Food

What's the most iconic fair food? Popcorn? Hot dogs? Deep-fried apple pie on a stick? Today, fair food and the fryer may be a match made in heaven, but where did the trend of eating adventurously at the fair start? Today, we're heading back to the original American fair: the Centennial Exposition of 1876. But don't get out the deep-fried twinkies just yet. Turns out, the biggest battle in 19th century American fair food was about fine dining! Despite the white tablecloth service visitors received in 1876, we'll learn how the Centennial Exposition saw the birth of some of America's most famous casual foods: the hamburger and soda.

Written & Produced by Laura Carlson

Technical Direction by Mike Portt

The Centennial Exposition:

May 10th to November 10th, 1876 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Considered to be the first World's Fair held in the United States, the Exhibition was also a celebration of the 100th Anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Over 35 countries were represented at the Exhibition, with demonstrations ranging from industry to technology to the arts. For the first time, individual States also were represented, with each featuring local products, produce, and livestock in specially-constructed buildings. For the first time at a World's Fair, women could display their handicrafts and skills at a special exhibition hall, known as the Women's Pavilion. An estimated ten million people attended the Exhibition, located in Fairmont Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

A Defence of American Cuisine

In the 19th century, American food was considered simple & rustic, appropriate for a bar snack, maybe, but not elegant dining. Harper's Weekly May 27, 1876

James W. Parkinson, 19th century Philadelphia restaurateur, in The Confectioner's Journal, 1875.

James W. Parkinson, famous Philadelphian restaurateur, bemoaned the low opinion of American food. In 1874, he wrote a lengthy defence of American produce, claiming the States' had the best food (and confectionary) in the world. He argued American food could hold its own against French cuisine, long considered to be the epitome of fine dining. He hoped the Centennial Exhibition would be the proving grounds for high-end American cuisine.

The Great American Restaurant, opened by Philadelphian wine merchants, Tobiason & Heilbrun, was the realization of a new kind of American restaurant, one which focused on a refined dining experience. The realization of Parkinson's dream, where a purely American cuisine could compete with French food, considered to be the epitome of high-end service and culinary ability at the time.

The End of the Great American Restaurant: After the Exhibition closed at the end of 1877, the building that once housed the Great American Restaurant was bundled up and carted away to become the Hotel Wellesly in Needham, Massachusetts, run as a Hygienic Village by William Emerson Baker, a kind-of east coast John Harvey Kellogg, who ran the hotel as a testament to public health and wholesome food. Intended to be a healthy get-away for New England’s rich and famous, it never made money & burned down in 1891.

The Restaurant of the South

As the United States attempted to knit itself back together after the Civil War, divisions remained. The Centennial Exhibition featured a Restaurant of the South within the fairgrounds, which advertised an image of southern plantation life, complete with live Dixie music.

French vs. American Cuisine: A Battle for Fine Dining

Despite James Parkinson's efforts, it was a hard sell convincing fair goers at the Centennial that American food could rival the haute cuisine of French food. The biggest rival for visitors' appetites to the Great American Restaurant was the Trois Fréres, a renowned Parisian restaurant which, despite closing four years earlier, had toured several international exhibitions as a "pop up" restaurant for eager diners.

A Battle for Class?

American cuisine in the mid-19th century was often seen as far more rustic and less genteel than French dining. Despite Parkinson's arguments that America had the best produce in the world, what was termed "American" food at the time was often billed as straightforward, cheap, and easy to eat on the go. Compare the wording in the two menus below, one from the French Lafayette Restaurant, the other from the more "American" Cafe Leland.

A menu from the Centennial Exhibition's Lafayette Restaurant which featured Parisian dishes.

Menu from the "American" Cafe Leland

The Origins of the "American Hamburger"?

Ph. J. Lauber's restaurant, also known as the German Restaurant or Centennial Restaurant. Centennial grounds, near Horticultural Hall. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia, Digital Collections

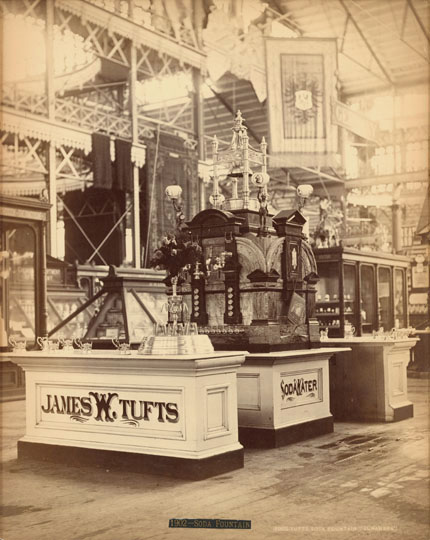

America's Love of Soda

One of the many soda water fountains on display throughout the Centennial Exhibition. Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Advertisement for Tufts' Soda Water, Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Baking a Better Loaf: Fleischmann's Compressed Yeast

Centennial exhibition Vienna model bakery, demonstrating the pressed/instant yeast of the Gaff, Fleischmann & Co., Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Fleischmann's Compressed Yeast, first debuted at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition at the Vienna Bakery. Fleischmann's company had figured out a way to dehydrate and preserve the yeast needed in baking. Before this, bakers had to use fresh yeast- easy to get, but impossible to store. Fleischmann's invention allowed bakers to store yeast in their cupboards for months at a time. Worrying that customers wouldn't trust the invention, they set up a bakery at the 1876 bakery where all products sold were made with the new dehydrated compressed yeast. The sales tactic was a hit & Fleischmann's company soon became the go-to brand for instant yeast- a reputation they still hold today in the United States & Canada.

The Buttery History of Butter Sculptures

Caroline Shawk Brooks, a farmer's wife from Arkansas, was the first to publicly display her butter sculptures at the Centennial Exposition. Her sculpture of "Dreaming Iolanthe" was such a hit at the Women's Pavilion that she was asked to demonstrate her skill with butter in the Main Exhibition Hall. After the Exhibition ended in late 1876, she continued to tour her skills with butter all over the United States, helping usher in the popularity of the "folk" sculptures at agricultural fairs and festivals ever since.

For more information, see Pamela H. Simpson's "Caroline Shawk Brooks: The Centennial Butter Sculptress" Woman's Art Journal Vol 28, No. 1 (Spring-Summer, 2007), pp. 29-36.

Great Books on the History of Fairs & Fair Food in the United States

Episode Soundtrack

Jon Luc Hefferman, "Epoch" (Epoch by Jon Luc Hefferman is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://needledrop.co )

Victor Herbert Orchestra, "1911-Jubel Overture (Weber)" (1911 - Jubel Overture (Weber)by Victor Herbert Orchestra is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.)

Victor Herbert Orchestra, "1909-Venetian Love Song" (1909 - Venetian Love Song by Victor Herbert Orchestra is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.)

Maciej Zolnowski, "Kwartet Japonski II" (Kwartet Japonski II by Maciej Żołnowski is licensed under a Attribution License.)

James I. Lent, "The Ragtime Drummer" (The Ragtime Drummer by James I. Lent is licensed under a Public Domain / Sound Recording Common Law Protection License.)

Andy G. Cohen, "A Perceptible Shift" (A Perceptible Shift by Andy G. Cohen is licensed under a Attribution License. )

Jahzzar, "Bodies" (Bodies by Jahzzar is licensed under a Attribution-ShareAlike License.)

Jahzzar, "The Lake" (The Lake by Jahzzar is licensed under a Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.)

Peter Rudenko, "Peace Within" (Peace Within by Peter Rudenkois licensed under a Attribution License.)